While gas prices in much of the country have gone down since their highs earlier this year, gas prices in California are soaring again, with prices almost exactly $1 per gallon more than they were a month ago. The average price in Los Angeles County was $6.41/gallon as of Sunday, October 9, while the statewide average was $6.33, according to AAA.

Since polls show this is one issue that does move the needle with California voters, while Gov. Gavin Newsom doesn’t seem to feel threatened by his GOP challenger, state Sen. Brian Dahle, he knows that his supermajority in both legislative houses could be threatened if potential voters are angry enough to make it to the polls.

So, in his trademark style, Newsom is “taking action.” First, he angry tweeted, but after being asked what he was going to actually do about it, well, of course, he’s going to call for a new tax. On the oil companies. To put money back in *our* pocket. Pretty sure that’s not how that works, but the bigger issue for Gavin is that the legislature has already adjourned for the year.

Once that was pointed out to him, he called for a special session of the legislature, to convene — a month after the election. Given that Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon appointed a commission to study the issue (to great fanfare) back in May and we’ve heard absolutely nothing from them, it seems that California Dems aren’t really interested in the true answer and would rather just blame “greedy oil companies” and tax them.

Here are the facts: Crude oil prices are DOWN. And yet…gas prices are up. That’s because greedy oil companies are ripping you off.

— Gavin Newsom (@GavinNewsom) October 6, 2022

They are raking in record profits at your expense.

I’m calling for a new tax on these corrupt oil companies to put money back in your pocket.

Any time Gavin Newsom says, “Here are the facts,” brace yourself — you will not be getting the facts.

The reasons for the recent spike in California gas prices was expertly laid out by Valero executive Scott Folwarkow in reply to a September 30 letter California Energy Commission Chair David Hochschild sent to California refinery executives regarding the issue. Hochschild’s letter was filed at the Commission at 1:26 p.m. that Friday afternoon, and he demanded a reply to his questions by Monday, October 3 — giving them just one business day to answer. The first paragraph of his letter reads:

I am writing regarding the sudden and unprecedented increase in prices at the pump this past week in California. As you know, crude oil prices are down and industry profits are up, yet gas prices have increased by a record $0.84 per gallon in 10 days in California — a $2.50 difference compared to U.S. prices. This degree of divergence from national prices hasn’t happened before, regardless of planned or unplanned refinery maintenance, and no explanation has been provided. The oil industry owes Californians answers.

Hochschild then asked pointed questions, but questions he should have already known the answers to.

1. Why have gasoline prices risen so dramatically in the past 10 days despite a sharp downturn in global crude prices, no significant unplanned refinery outages in the state, and no increases in state taxes or fees?

2. If logistics or other obstacles have contributed to the price increases, what measures could the State of California take to address them without sacrificing environmental or public safety concerns?

3. Why did refiners allow inventory levels to drop when they have known for months, or in some cases years, that planned maintenance would occur at this time?

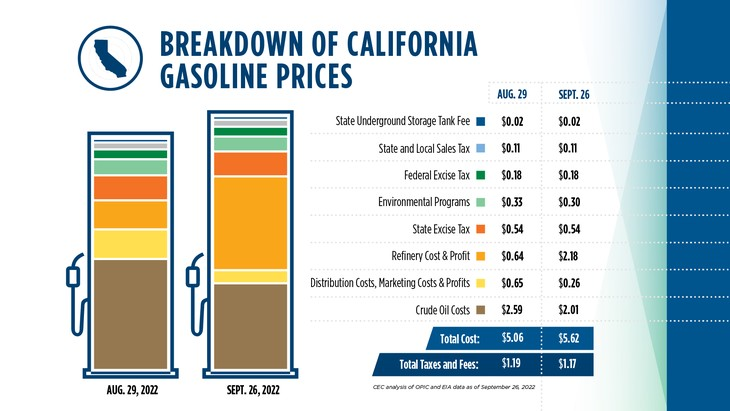

In comments made to accompany his letter, Hochschild dismissed any claim that gas prices increased because of drilling permitting issues, stating that the price increase is occurring at the refining stage. Refinery cost and profit per gallon went from $0.64 on August 29 to $2.18 on September 26.

We all know that in general, the costs are higher due to the additional taxes and regulations Golden State legislators have so (un)intelligently enacted, but Valero’s reply letter to the California Energy Commission gives specific reasons for both higher costs in general and this particular sharp increase and is written so that most laypeople can easily understand it.

Folwarkow starts by dismissing the oft-repeated claim by lefties that there is some kind of price gouging conspiracy among oil companies, noting:

Ironically, on the same day we received the Commission’s letter, a federal judge in a 103-page reasoned order, following review of thousands of pages of documents and hours of depositions and discovery, yet again threw out another case alleging price conspiracies by the fuel industry finding no basis for the allegations.

After informing the Commission that he can only be so specific in his answers without giving away trade secret information, Folwarkow confirmed that yes, Valero has planned maintenance activity underway at one of their two refineries in the state — maintenance that’s “required to keep the refinery running safely and properly and to meet the regulatory expectations of the state.” That’s pretty important.

Mr. Folwarkow educates Hochschild and, by extension, Gavin Newsom, on supply chain resiliency, and on the fact that you can’t enact cap-and-trade fees and other burdensome environmental regulations without affecting the number of refineries in your state, decreasing refining capacity, and ultimately increasing prices.

As to separation between California prices and the prices in the rest of the United States, we can offer the following information. For Valero, California is the most expensive operating environment in the country and a very hostile regulatory environment for refining. California policy makers have knowingly adopted policies with the expressed intent of eliminating the refinery sector. California requires refiners to pay very high carbon cap and trade fees and burdened gasoline with cost of the low carbon fuel standards. With the backdrop of these policies, not surprisingly, California has seen refineries completely close or shut down major units. When you shut down refinery operations, you limit the resilience of the supply chain.

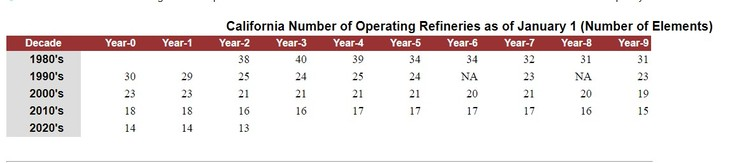

Indeed, US Energy Information Administration (EIA) statistics show that the number of operating refineries in the state has decreased dramatically over the years. In 2000 there were 23 operating refineries, compared to just 13 in 2022. In 1983, when the state’s population was 25 million, there were 40 operating refineries. In 2020 there were 40 million people in California and just 14 operating refineries. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that that’s a problem.

Newsom and his surrogates have suggested that fuel companies aren’t holding enough product in reserve to keep supply flowing when refineries are unexpectedly forced to shut down, or even during planned outages. Not so, says Valero:

We have made appropriate arrangements to source supply and/or intermediates to keep our refinery at as close to full rate as possible. We also either built inventory or arranged for additional supply to assure we meet our contractual obligations to our customers. Valero does this when we have the opportunity to plan for a significant outage. This maintenance turnaround was handled no differently.

Overall, Folwarkow said Valero attempts to maintain a certain level of inventory on hand, but that their supply has been tight and they’ve pulled down inventory to meet demand — something they believe the state government would want them to do to avoid price increases.

Many commentators have noted that California’s special fuel blend (mandated by the state) causes cost issues, and it does. An industry executive whose company runs two of the state’s 13 operating refineries has a bit more credibility when imparting that information and expanding upon it (emphasis mine):

From the perspective of a refiner and fuel supplier, California is the most challenging market to serve in the United States for several additional reasons. California regulators have mandated a unique blend of gasoline that is not readily available outside of the West Coast. California is largely isolated from the fuel markets of the central and eastern United States. California has imposed some of the most aggressive, and thus expensive and limiting, environmental regulatory requirements in the world. California policies have made it difficult to increase refining capacity and have prevented supply projects to lower operating costs of refineries.

The last paragraph wraps it up perfectly:

We believe the Commission experts understand that California cannot mandate a unique fuel that is not readily unavailable outside of the West Coast and then burden or eliminate California refining capacity and expect to have robust fuel supplies. Adding further costs, in the form of new taxes or regulatory constraints, will only further strain the fuel market and adversely impact refiners and ultimately those costs will pass to California consumers.

It’s written so simply that even Newsom should be able to understand it. But will he?